On Being a Black and Asian Mixed Race Woman

SOCIAL IDENTITY | LIVED EXPERIENCE | My mother is a British Black Caribbean woman, and my absent father is a British Asian Pakistani or Iraqi man. When questioned about my…

My mother is a British Black Caribbean woman, and my absent father is a British Asian Pakistani or Iraqi man. When questioned about my ethnicity , a question I frequently received throughout my life , I would respond with, "I’m Mixed with Black and Asian," and reactions would differ from person to person.

Some would not believe me whilst others would say, "Oh, you look more Black, you know, have more Black features." "So, you’re mainly Black then?" Dealing with the constant erasure of my identity coupled with never meeting my father bred thoughts of inadequacy from an early age and forced me to co-opt a dissembled belief that I was not a "true Mixed" woman.

Upon reading Mixed/Other: Explorations of Multiraciality in Modern Britain by Natalie Morris, I religiously perused chapter five, "The 'Right Type of Mix' and "Minority Mixes." This was the first time in my twenty-one years of life that I finally felt seen.

Morris writes, If you’re mixed with two non-white ethnicities, society loses interest. Anything beyond this binary is categorised a 'other' and the intricacies and nuances of your heritage are not deemed worthy of wider discussion, or even clear categorisation. Just take a quick look at the options on the [UK] census and ethnicity forms. There are three distinct categories for mixed individuals to tick: white and Black Caribbean, white and Black African, white and Asian. Then at the bottom, there is a fourth category: "other mixed." This is a singular option for the myriad ethnicity potentials within the mixed experience that don’t include whiteness. It sends a message that so-called 'minority mix' ethnicities hold less value than mixes that include whiteness. Mixed/Other: Explorations of Multiraciality in Modern Britain by Natalie Morris (2021).

Expanding on Morris’ point, anytime I would fill out forms that asked the much-dreaded ethnicity question, it would put me in a state of distress and unease. Questions like "Why isn’t there a Black and Asian mix option?" to "Why is my identity being overlooked?" would float around my head and would escalate to extremes of "Do I even exist?"

As a child, my peers would say, "You’re not mixed. You have to be half Black and half White to be mixed." Of course, these were only children but being only ten to fifteen years ago, the way that society views minority Mixed Race people has not changed much.

Mixed Race representation in media has widened since then but only in the scope of Black and White Mixes. Interracial couples on television comprise a Black parent (usually the father) and a White parent (usually the mother). A disservice to those of us who have a non-White ethnic background, this essentially whitewashes the Mixed Race identity and further gatekeeps what qualifies as being Mixed Race. In short, representation must become more conscious and inclusive of the plethora of Mixed Race ethnicities that exist.

As an adult (at the time of writing this), I exorcise my half-Asian ethnicity and embrace being fully Black instead. Yes, I know this isn’t healthy. Yes, I know this is counterproductive. But, I am tired of being questioned and, at times, fetishised for being of an "unusual" mixed lineage. Affirming that I am "proud to be Black" has truth in it, but also a defence mechanism to my own insecurities of not looking or being "Asian enough."

Afro-textured hair and my now darker-than-average mixed-race skin tone made me Black passing and I used that as a shield of protection against the naysayers and the men who only sought to get into a sexually charged relationship with a minority (also known as "exotic" to their fetishism), Mixed woman.

In Morris’ book, Jeanette, who is of Filipino and Cameroonian mixed descent, eloquently expresses her experiences growing up as a minority Mixed person.

People are taken aback when Jeanette tells them she’s mixed. She says there is still a very blinkered and limited expectation of what 'mixed' means, and with her dark skin tone and more typically Asian facial features, Jeanette doesn’t fit that blueprint. "When I was growing up, people only saw me as Black. The landscape is different now and people are more likely to be aware that I might be mixed, but back then there was so little understanding. As a result, I always saw myself as "other" or Black rather than mixed." — Mixed/Other: Explorations of Multiraciality in Modern Britain’ by Natalie Morris (2021).

Jeanette’s words are a vital and visceral testament to my own experiences and encounters. I, too, was always denied my Mixed Race identity. Now that I usually identify as being fully Black, certain family members are quick to remind me that I am not fully Black. "Kashala, stop forcing it. You’re not Black like me. You’re mixed."

Excluded from being Mixed Race and excluded, by some, from being Black has left large fragments of confusion and ostracisation that took years to unpack. In fact, I am still dealing with the nuances and cultural issues today.

How do I manoeuvre in society and find a sense of belonging?

How do I heal?

I may not ever find a sense of kinship or belonging, but I will learn to accept myself for who I am. And with that, I will tell you again.

My mother is a British Black Caribbean woman, and my absent father is a British Asian Pakistani or Iraqi man. My name is Kashala Abrahams and I am a mixed-other woman of British Black Caribbean and British Asian Pakistani or Iraqi descent. I exist, and I matter.

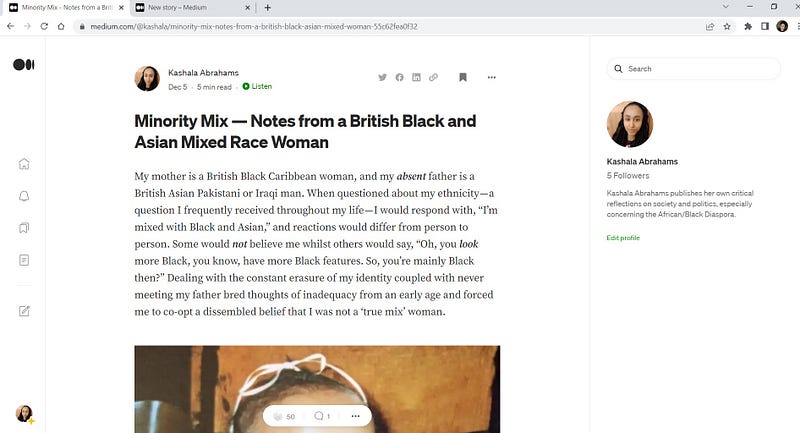

- Edit changes made on the 7th of December 2022: I wrote the original article on the 5th of December 2022 under the title 'Minority Mix — Notes from a British Black Asian Mixed Woman' and then changed that article’s title to 'Minority Mix — Notes from a British Black and Asian Mixed Race Woman' on the 6th of December 2022 to improve readability and understanding of my racial background.

However, after a conversation with my mother about my absent father, I decided to delete that article and republish it under the title 'On Being a Black and Asian Mixed Race Woman' on the 7th of December 2022. The original article was deleted but the URL of the original article was https://medium.com/@kashala/minority-mix-notes-from-a-british-black-asian-mixed-woman-55c62fea0f32

Please see the image below.

- Edit changes November 2025: As I am preparing for my MSc in Psychology Conversion degree, I edited the grammar style of this article to reflect a relaxed APA 7th edition style guide.